The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) has announced that from late September commercial operators piloting a drone weighing less than 2kg will not need regulatory approval.

This removes the need to obtain an operator’s certificate costing $4000 and remote pilot licence, both currently required for any commercial operation.

While the red tape restricting commercial drone piloting in Australia has been cut, a sufficient number of horror stories involving drones could have easily pushed CASA in the opposite direction.

There’s little doubt that Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) industry leader, DJI, is aware how dangerous its products can be: from gory propeller accidents and costly malfunctions; to interfering with emergency situations and invasions of privacy.

DJI’s latest model, the Phantom 4, has drastically improved safety features, along with other improvements – a wise ‘pre-emptive’ move given the survival of this emerging industry needs aviation authorities to stay on its side.

The new laws state that commercial operators ‘simply need to notify CASA that they intend to use very small remotely piloted aircraft for commercial flights according to a set of standard operating conditions’.

These mandatory conditions include flying only during the day in visual line of sight and below 120 metres; keeping more than 30 metres away from other people; flying more than 5.5km from controlled aerodromes; and not operating near emergency situations.

CASA will provide an easy-to-use online notification system.

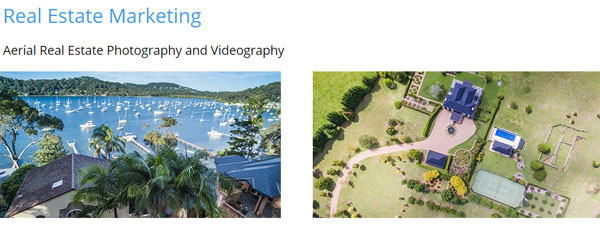

Private landholders are permitted to fly drones weighing up to 25kg on their land for commercial reasons with no CASA approval required. This is good news for photographers and videographers using drones for industrial purposes such as 3D mapping, agriculture, land surveying, real estate, etc.

‘While safety must always come first, CASA’s aim is to lighten the regulatory requirements where we can,’ said Mark Skidmore, CASA’s director of aviation safety. ‘The amended regulations recognise the different safety risks posed by different types of remotely piloted aircraft.

‘People intending to utilise the new very small category of commercial operations should understand this can only be done if the standard operating conditions are strictly followed and CASA is notified. Penalties can apply if these conditions are not met.’

The ‘small category of commercial operations’ practically all relate to aerial photography and videography.

Real estate photography has radically changed since consumer UAV’s were introduced. In the beginning they were mostly used to market stately piles, but Craig Newlyn, director of Droneheadz, a Sydney-based aerial photo business, has noticed more affordable homes now being promoted with drone photos.

‘Demand for real estate aerial videos and photos is extremely high. In the last 12 months it has grown dramatically. It used to be that only the multimillion-dollar properties would value aerial shots as a part of their sales campaign, but not any more,’ he said to real estate portal, Domain. ‘Properties right across the market at all price points are now using drones for advertising.’

A real estate and wedding photographer told ProCounter he bought his first drone in 2013, and as an early adopter of the technology scored additional clients in both fields of work.

He opted for anonymity as he never obtained the $4000 licence to commercially fly his DJI Phantom 1. While he follows the recreational safety rules outlined by CASA, along with many other professional photographers he cannot justify the cost, time and effort required by current regulation.

It’s virtually impossible for CASA to catch anyone flying a drone commercially against regulation unless an accident occurs or is reported. (Or if the photographer admits to it in an article and has his or her name published!)

For this photographer the unmanned aircraft is 75 percent gimmick and 25 percent a tool. It has paid for itself around four times over ( and he’s up to his third Phantom 1) but is essentially a fun, quirky addition to the service he offers.

This still was taken at Princes Pier in Melbourne by photographer Zhongda Wang as part of a uni project. He used the DJI Inspire 1 – a pro-oriented drone that weighs over 2kg. Source: Flickr.com/zeropmel.

‘When I first started using them three years ago no one had seen one. The first time I ever did it (during a wedding), I surprised the wedding party with it and there was a great gasp. Everyone was absolutely amazed and I hovered it there for about a minute – 12 photos – and in the end I got great photos,’ he said. ‘It was a fantastic talking point. I brought the thing back down, the bride and groom rushed over – they didn’t expect or know anything about it – and I took the camera off and passed it around the wedding party.

‘That got me four or five weddings after that – it was novel. Now it’s no longer nearly as novel as most guests have seen drones but it still does create a bit of fun. I only use it for a group photo. It’s part of my package.’

The same scenario applies for real estate work.

‘In our particular area – we are in a slightly semi-rural area – any five acre block is well and truly enhanced by a drone photo.’

He adds that it is also handy to show a house in reference to the town centre or school, and while he was the first in the area using a drone there are three or four other local real estate photographers on board. It’s fast becoming an essential part of real estate marketing.

The photographer’s Phantom 1 is a fairly primitive beast compared to today’s models. It has a battery life of about five minutes and doesn’t have a built-in camera – he rigged a compact Nikon 1 J1 10.1 megapixel camera to it himself. He doesn’t have a first person view of the drone from an iPad like new Phantom models, and no safety features. (Compare that to the DJI Phantom 4 below)

He has kept it this long because of his heavy investment in the batteries – he has 12 spares. While he has looked at the latest release from DJI with admiration, it’s currently too much for the budget.

The technology has many more applications for professional photographers and CASA cutting the red tape will ideally persuade those unsure about the future of regulations to purchase a UAV. ‘The skies the limit’, if you will.

Over a year ago a CASA spokesperson told ProCounter major changes wouldn’t be implemented ‘for two or more years’, and the rules will likely ‘become stricter’. So why the change?

DJI, which has 70 percent market share, is slowly rolling out a ‘geofencing system’ in the controller app which it calls Geospatial Environment Online. This blocks its aircraft from venturing into restricted airspace which includes nearby airports, over major sporting events, specific landmarks and buildings, as well as temporary no-fly zones during emergency situations such as a bushfire.

DJI says it’s constantly expanding the system. As of last year the DJI Phantom 3 and Inspire 1 Pro cannot fly within 2.4 to 8km of Australia’s 10 major airports.

‘I’m very encouraged that a manufacturer is taking that step because unmanned aircraft of that type… may create hazards for other aircraft,’ Reece Clothier, an aerospace engineer who worked with CASA on the new regulations, told the ABC last year. ‘So building in safety devices like DJI is doing is a great catch to prevent those situations from happening.

The new f2.8 aspherical lens on the Phantom 4 has ‘a 94° field of view, reduces distortion by 36 percent and chromatic aberration by 56 percent when compared to a Phantom 3 lens. A hyperfocal length of one meter allows you to get closer to objects while keeping them in pin-sharp focus’.

The DJI Phantom 4

DJI’s Phantom 4 quadcopter, a ‘flying camera’ with 4k video at 30fps (1080p at 120fps), is available in a couple weeks for $2400 including GST.

The drone weighs less than 2kg, and has a built-in 4k camera capable of capturing 12-megapixel RAW stills. (All Phantom drones are under the 2kg restriction, however the Inspire pro-oriented models weigh more and have a much larger payload.)

It has an improved 3-axis gimbal housed in the body which removes vibration and movement in-flight for smoother footage during manoeuvres. Battery life is 28 minutes when flown conservatively – a 25 percent increase from the previous model – and it can fly 5km from the operator, who has a live first-person view from the controller.

ProCounter attended the Phantom 4 media briefing and piloted the drone in CR Kennedy’s Melbourne Office car park, under the guidance of Adam Najberg, DJI global director of communications.

The drone was remarkably easy to fly. Movement is controlled by one joystick while another controls elevation and pivoting the drone’s position. It hovers on the spot when no controls are pressed. But if it’s turned to Sports Mode it can fly at over 60km/h, meaning the controls are far more sensitive and challenging.

Unfavourable weather conditions could also present a challenge. However when it hovers and is knocked by a person’s hand – as was demonstrated – the drone remains firmly in place.

A new feature is visual tracking, where an operator circles a person/moving object on the remote control and the drone follows them. It lost the demonstrator once or twice as he ran and dodged between vehicles, but overall does well to keep a moving object in the frame.

Previous models tracked a GPS beacon on a person.

An appealing new safety feature which may help prevent damage to the $2400 quadcopter is multiple obstacle sensors.

Two sensors on the front detect objects facing the Phantom. It will first beep a warning at the operator before coming to a hovering stop even if the operator tries hard to collide it into an object – humans, trees, vehicles and so on. However nothing will stop it flying sideways into something.

In the tracking mode it also detects objects facing it when following someone. If it all becomes too much, an operator can active ‘Smart Return Home’, which automatically and safely brings it back to the take-off location.

The wedding photographer ProCounter spoke with said the one ‘absolutely vital’ improvement he’d like to see in drone technology is obstacle avoidance, and commended DJI for implementing it.

While the safety sensors and tracking are yet to be perfected – this is the first DJI model to use this technology – it’s an indication of where DJI plans to focus innovation beyond the gimbal, camera and lens.

If DJI’s ‘safety first’ approach is successful everyone wins – aviation authorities will stay happy with no pressure to crack down on illegal drone operators, and photographers won’t need to fork out thousands for a licence.

– Check out Zhongda Wang’s other photos here.