More families are requesting their departed loved ones’ funeral ceremonies are captured in photographs.

Photographing a funeral presents a unique set of challenges. It’s an emotional family event commemorating the person’s life, and photographers may rightly feel out of place attempting to document it.

Photographing a funeral presents a unique set of challenges. It’s an emotional family event commemorating the person’s life, and photographers may rightly feel out of place attempting to document it.

In 2007 John Slaytor (right) quit his day job to pursue a career in photography. He shot weddings and christenings, and didn’t expect that a decade later he’d be known as The Funeral Photographer.

Funerals have now become John’s main source of income.

It started after he showed his neighbour a photo album of people and places he captured while visiting India. Noticing John’s unobtrusive and candid style of photography, the neighbour asked him to photograph his uncle’s funeral.

The award-winning photographer now captures roughly one funeral a week, and receives requests from all over the country.

‘I find the work fascinating. It’s riveting for me. It’s about focusing on compassion,’ John told ProCounter. ‘I’m never going to photograph great moments in history, but I’m about photographing the subtleness of human gestures. People being kind to each other. It’s what makes my photography meaningful. A daughter reaching out to her mother by the grave site – these small gestures. They’re amazing, and I’m honoured to capture them.’

The market for funeral photography is growing, John said. Demand isn’t massive and the supply of photographers remain low, but clients are becoming more open to the concept.

John’s clients mostly find him through Google. His website, thefuneralphotographer.com.au, provides the business visibility through a focus on Search Engine Optimisation (SEO).

A recent online discussion among Australian Institute of Professional Photography (AIPP) members indicate a few photographers are occasionally asked to capture a funeral. Some revealed they had shot several funerals with varying degrees of difficulty, one person said they wouldn’t do it again, while others politely declined a client’s request.

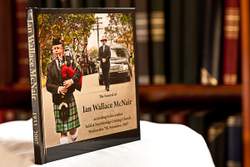

John offers two types of packages; both include a custom-made photo book.

He says the photo book is an integral part of his business – he spends as much time designing books as he does at the funeral. A CD of image files is available for an additional fee, either $160 or $180.

‘I didn’t want to go down the route of handing out CDs or selling image files. I think that’s tacky for what I do. People aren’t always aware they want the book, but clients say that as time goes on it becomes more and more important to the family.’

John says in instances where an elderly person has died, leaving behind their partner who has had a stroke or Alzheimer’s disease, the book is invaluable for the family.

‘The surviving spouse may then ask where their partner is, and the family can show them the book to help explain they died,’ he said.

John designs the books through Photobook Australia. He’s tested most custom photo book printing outlets, but found Photobook Australia quickly delivers high quality books, and provides him creative freedom.

Photographing a funeral

John says that it’s pivotal to be seen with key family members at the beginning of the day – both photographing and talking with them. He wouldn’t photograph a funeral without it being known he’s there at the request of the family, and not some random weirdo off the street.

Sometimes he’s mentioned during the service, or in the printed funeral program.

In 10 years, he’s only received one complaint.

John’s noticing more guests obstructing his view by taking their own snaps – an irritating situation wedding photographers are familiar with!

Flash is almost never appropriate, and John prefers shooting with a 130mm or 24mm lens combination.

The funeral photographer describes the style as candid and unobtrusive. He tries to remain unnoticeable – a fly-on-the-wall approach, capturing subtle natural moments. No posing is done unless a family portrait is requested after the formal proceedings take place.

Asked if his style is photojournalistic, John says no – ‘photojournalism can be a bit unkind, whereas my approach is more sympathetic. I try to be kind to the people I photograph’.

But he doesn’t avoid capturing any shots.

‘I’m a stranger to the family, and haven’t had a great deal of contact. So I tend to photograph everything and let them decide what they want,’ he said. ‘Often they’ll say, for example, that they want photos of the body. But so often those photos don’t end up in the book.’

John recently purchased the Nikon D850, but is tempted to move to Sony’s mirrorless cameras. The silent shutter, continuous eye AF, and impressive range of high-end glass is enticing for a funeral photographer.

While his now-retired D4 was great, the camera shutter sounds like a ‘machine gun’ in burst fire. Not exactly ideal at a solemn event.

It’s important to have a camera with good low-light capabilities given most images need to be flash-free and churches generally have dim lighting.

John understands most photographers may not be comfortable shooting a funeral. It’s an odd niche. But he’s carved a rewarding career from it, and believes the work makes a lasting impact on his clients.