Shooting The Picture, a book hot off the press by Fay Anderson and Sally Young, will quench the thirst of any reader craving an in-depth historical account of press photography in Australia.

It’s likely the first of its kind to piece together the fragmented history of Australian press photography, and in doing so offers an insightful gaze into an ever-changing industry.

It’s likely the first of its kind to piece together the fragmented history of Australian press photography, and in doing so offers an insightful gaze into an ever-changing industry.

In equal parts it’s also a contemporary history lesson. Distinguished journalist Michael Gawenda writes in the foreword that words are consumed and forgotten, but a great news photo lingers forever in the mind and transcends time.

The dynamic relationship between photography and pivotal moments in time appears throughout the book. While it’s photographers documenting these moments, as often as not these moments also change photography.

It’s woven together with authority from extensive interviews with 60 photographers, editors and journalists – with Young clocking the longest interview at eight or nine hours! These first hand accounts are accompanied by 95 photos representing a timeline of Australian photojournalism. A difficult task, given there were millions of images to choose from.

‘Our selections and omissions should not be read as a judgement about quality (of press photography),’ the writers say in the Preface. ‘…We tried to select photographs that illustrate shifts and traditions in photography practice, technology, newspaper values, photographers’ working conditions and rituals, collective memory, and social changes affecting audience reception of photographs.’

However iconic images do appear, such as Mervyn Bishop’s photo of Gough Whitlam pouring soil into the hand of Gurindji landowner Vincent Lingiari in 1975.

The opening chapter tracks the first photo published in an Australian paper. Had the technology existed it would have likely began in 1880 with the dead bodies of Ned Kelly’s gang.

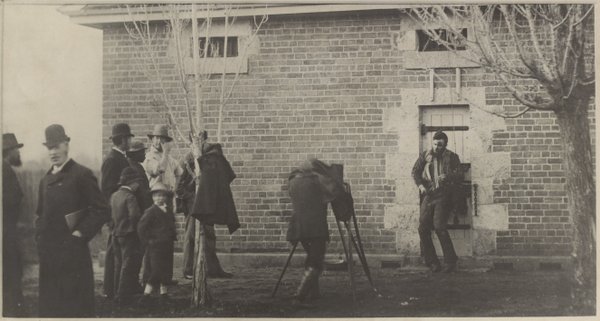

Joe Byrne’s body outside Benalla Police Station, sepia photograph by JW Lindt, 29 June 1880. The man with the sketch book under his arm to the left would draw an illustration for a newspaper. This photographer was shooting for police. Source: Supplied/State Library Victoria Pictures Collection.

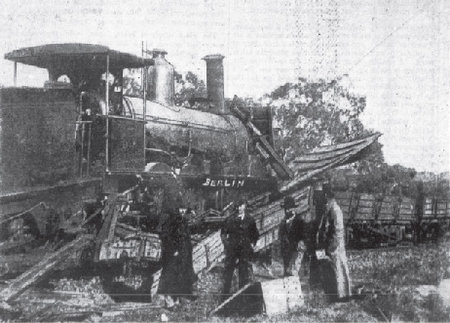

It would be eight years later, in 1888 that Young and Anderson speculate the first photo appeared in a newspaper. The photo was of a railway accident captured by George Berlin and printed in the weekly Sydney Mail, owned by John Fairfax & Sons.

The ‘half-tone technique’ was the method used – setting a photo onto the same printing plate and using different sized dots and spacing to press the photo.

This photo was also the first example of an Australian photographer manipulating and tampering with a news photo!

Berlin painted his name onto the train wreckage for credit. Unethical by today’s standards, but intuitive as photographers wouldn’t be given bylines until a hundred years later.

Railway accident at Young, photograph by George Berlin. 15 Sept 1888. Sydney Mail 558. Source: National Library of Australia.

‘When photographs came on board (at newspapers) – particularly the broadsheets – said this is “low brow stuff”, and “this isn’t what news is about, we don’t want this in papers”,’ Young said in an interview with ABC. ‘Eventually they saw the success of tabloid newspapers. The Sun News Pictorial deliberately started up in the 1920s as a pictorial newspaper.’

She observed that news outlets have always been slow to embrace change. The resistance to creating a profitable online business model in the early days of the internet being a recent example.

Accessibly academic

Fay and Anderson began work in 2012 on Shooting The Picture, made possible by a three year grant from the Australian Research Council – a government funding scheme for research projects.

The research is academic, as is the writing style.

This makes Shooting The Picture belong first-and-foremost at university and public libraries across the country. It has invaluable information for students.

However those with an interest in photography, photojournalism, and contemporary history will take pleasure in owning and delving into this book.

Anderson, an associate professor at Monash University’s School of Media, Film and Journalism; and Young, a professor in political science, could have steered the book in any number of directions, but chose to focus on national news and ‘papers that survived the twentieth century.

The writing is not dry or lacking punch or expression – often a downfall for many ‘text books’ that become detached from a non-academic audience.

Perhaps the hundreds of hours spent hearing stories and opinions from photographers, along with the authors’ expert understanding of the media landscape, allows the narrative to flow as it were a giant in-depth feature article.

Half the interviewees are retired. Photographers like Barry Norman, Keith Barlow, Ray Blackburn, Lloyd Brown all entered the newsroom before the 1960s and offer an insight into an industry of men armed with heavy Speed Graphic cameras.

Contemporary press photographers – or photojournalists as they’re known today – like Mike Bowers, Andrew Chapman, Kate Geraghty, Stephen Dupont, Andrew Meares, Nick Moir and countless others offer their take on the industry and their experience.

The book has 406-pages. It isn’t nearly the whole story, the authors’ write. Choices were made about what was to be cut, which they liken to a photographer deciding what is shown in the frame and from what angle the photo is taken.

However, like any great photograph, those choices illustrate the story.

The industry was a boys’ club up until the 1970s. Suits and ties were mandatory, as were drinks at the pub after work.

Photographers possibly working during the royal tour in 1954. Courtesy of Bryan Charlton. Photographer and copyright unknown.

Workplace sexism kept most women photographers out – the justification was the equipment was too heavy. That changed in the 1970s due to social change but also technological change. Rolleiflex cameras phased out and ‘sexy’ 35mm Nikon cameras became the go-to for press photographers.

The 1980s saw another industry shift, unrelated to technology. Universities began teaching press photography and journalism, shifting it from a working-class job into a somewhat glamorous middle-class profession.

With heightened competition from tertiary-educated talent, press photography became more ‘artistic’.

All photographers in Shooting The Picture recall fond memories from the darkroom. The authors seamlessly weave photographers’ stories together to have them finish or add to each other’s experience.

It was mostly described as a ‘magic’ place, where seniors shared techniques with cadets – who are now award-winning photographers.

The digital age

In Australia it was the 2000 Sydney Olympics that saw a mass roll out of digital cameras.

Digital existed before then, however it was hugely expensive. Grant Wells, chief photographer for Tasmania’s The Advocate, estimates it cost the paper $250,000 to arm five photographers with the gear in 1999.

And once digital came around, so did the redundancies.

‘A lot of the photographers we spoke to said there’d been times of redundancy before at newspapers, but something very different is going on now,’ Young said. ‘What the major newspapers that are left are doing are using agency photos and stock photos a lot more. Or, they’re arming their journalists with stock photos and saying: “You take the photos”. Perhaps unintentionally, we’ve captured the tail-end of a phenomenon.’

Press photography is about more than a photo, and this is made clear in Shooting The Picture.

It’s about visual representation and documentation of political leaders and events, crime and the body, war and censorship, international events, disaster and trauma, sport, celebrity, gender, race and migration.

Shooting The Picture is available in paperback for $45, or e-book for $22.99. Click here.